Rosetta Stones and Mazes: Maze Design

Prerequisites

Before starting, readers should

- be familiar with the basics of their computer terminal and its character printing.

- understand the basics of fonts and how special fonts are needed in order to print some icons, glyphs, and Unicode characters

- be familiar with binary representation of numbers.

- understand some basic bitwise operations.

Outline

By the end of this post, readers will

- understand the grid of most terminals.

- be familiar with helpful Unicode characters for maze building.

- understand basic bit encoding within integers as it relates to maze building.

- gain some tips for their own attempt at building mazes with this design.

Checklist

Recall the language feature hit and miss table from the previous post in this series.

| Hit | Miss |

|---|---|

| Basic Control Flow | Common Textbook Algorithms |

| Associative Containers | Recursion |

| Sorting | Bit Manipulation |

| File IO | Composition |

| Standard Output | Multithreading/Processes |

| Build Systems | 3rd Party Libraries |

| Command Line Arguments | Type Creation |

| Functions | Interface Design |

| Tests | Trees |

| Strings | Stacks |

| Heaps | |

| Queues | |

| Graphs | |

| Multidimensional Arrays | |

| Fun! |

This referred to the features a word counting program hit and missed as a “Rosetta Stone” candidate. Let’s convert it to just a hit table, and we will fill in how we hit all of these points as we go through the series. This article hits the following points.

| Hit | How |

|---|---|

| Basic Control Flow | Sequentially building a maze. |

| Associative Containers | Maze building algorithms. |

| Sorting | Maze building algorithms. |

| File IO | Output to terminal with stdout. |

| Standard Output | Printing maze walls to terminal. |

| Build Systems | Setting up the project. |

| Command Line Arguments | Maze size input to program and algorithm selection. |

| Functions | Any maze building function. |

| Tests | Immediate feedback from terminal. |

| Strings | Command line argument and maze character printing. |

| Common Textbook Algorithms | Maze building algorithms. |

| Recursion | Maze building algorithms. |

| Bit Manipulation | Maze wall design. |

| Composition | |

| Multithreading/Processes | |

| 3rd Party Libraries | |

| Type Creation | Maze wall design. |

| Interface Design | |

| Trees | Maze building algorithms. |

| Stacks | Maze building algorithms. |

| Heaps | Maze building algorithms. |

| Queues | |

| Graphs | Maze building algorithms. |

| Multidimensional Arrays | Maze square storage. |

| Fun! | All of it! |

Choose a Language

Previously, I proposed that building and solving a maze is the ideal Rosetta Stone program. If you attempted to implement the program before arriving here as suggested, great work! Perhaps you are wondering how an implementation is supposed to check off the wide range of language features mentioned in the Hit and Miss table from the first post. This post will discuss some design choices you can make to check off as many language features as possible with a maze program.

For this series I will choose Rust as my sample language when discussing design decisions. If you select another language you will inevitably run into some language features that force you to change the design and that is OK.

Maze Architecture

First, we will design the maze itself. Because we are operating in the terminal we should become familiar with the grid available to use.

The Terminal Grid

The above grid represents the cells of a computer terminal. Each cell is rectangular, being slightly stretched vertically. We can think of the height as roughly double the width. This will become important to consider when trying to make mazes that look good in the terminal. For example, a common first attempt at a maze will often look something like this.

+-------+---+

|S | |

+-----+ +-+ +

| | |

+---+ + +---+

| | |

+-+ +-+ + + +

| | | | |

+ +-+ +-+ +-+

| | | |

+-+ + +-----+

| F

+-----------+

Using a combination of ASCII characters allows us to create a somewhat recognizable maze structure. However, due to rectangular cells the gaps between the vertical bars and the plus signs can seem like paths when in fact they are not. If we look to Unicode we can discover some characters that are tailor-made to our task of building paths and walls.

Box-drawing Characters

One of my favorite Wikipedia pages is the Box-drawing characters page. The general purpose of these characters is to address the problems we saw with the tiny gaps in our attempt at mazes with ASCII characters. I frequently find myself visiting this page when writing documentation or diagrams for projects I am working on. It is very satisfying to have lines appear to seamlessly connect in a terminal or editor.

While traditionally intended to help create clean terminal user interfaces, box-drawing characters can also help us in our maze endeavors. What are mazes if not boxes with little chunks taken out to form paths? Let’s examine characters that the Wikipedia page provides to us in the order they are presented. Here is the lightweight variant of box-drawing characters we are most interested in.

─ │ ┌ ┐ └ ┘ ├ ┤ ┬ ┴ ┼ ╴ ╵ ╶ ╷

Maybe you already have a vision for how these pieces could fit together to create a maze. We have lines, corners, and intersections. Just as a test, let’s redo our ASCII maze with these pieces.

┌───────┬───┐

│S │ │

├─────┐ └─╴ │

│ │ │

├───╴ │ ╶───┤

│ │ │

├─┐ ╶─┘ ╷ ╷ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ └─┐ ┌─┘ └─┤

│ │ │ │

├─╴ ╵ └─────┘

│ F

└───────────╴

Much better! The walls are solid, and it is clear where the paths lead. However, I generated the above maze by hand which is not a viable solution for a maze generation program. Let’s design a module that will help us program the process.

Bit Encoding

So far we know two important facts.

- The terminal for your computer acts as a grid with rectangular cells for characters.

- Unicode box-drawing characters can cleanly connect lines in these cells.

We can now prepare our own abstraction for how we will represent and modify terminal cells to represent a maze in memory during our program.

Every cell will be represented as a Square with Rust’s u32 type. Here, u32 means that this is an unsigned 32-bit integer, giving us 32 bits for our design. For any square in our maze we know it is either a path or a wall. If the square is a path, we will use a bit to indicate this. If the square is a wall, 4 of these 32 bits will specify its design. We will also add a WallLine type just for clarity to know that we are dealing with a wall and not a path sometimes in our code.

// walls─────────┬┬┬┐

// path bit───┐ ││││

// 0b0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

pub type Square = u32;

pub type WallLine = u32;

If we count our bits in this diagram starting from right at 0 to left at 31, representing the least significant bit to most significant bit, bits 24-27 will represent our walls and bit 29 will mark a Square as a path. Do not worry about all the bits going to waste for now. They will be used later.

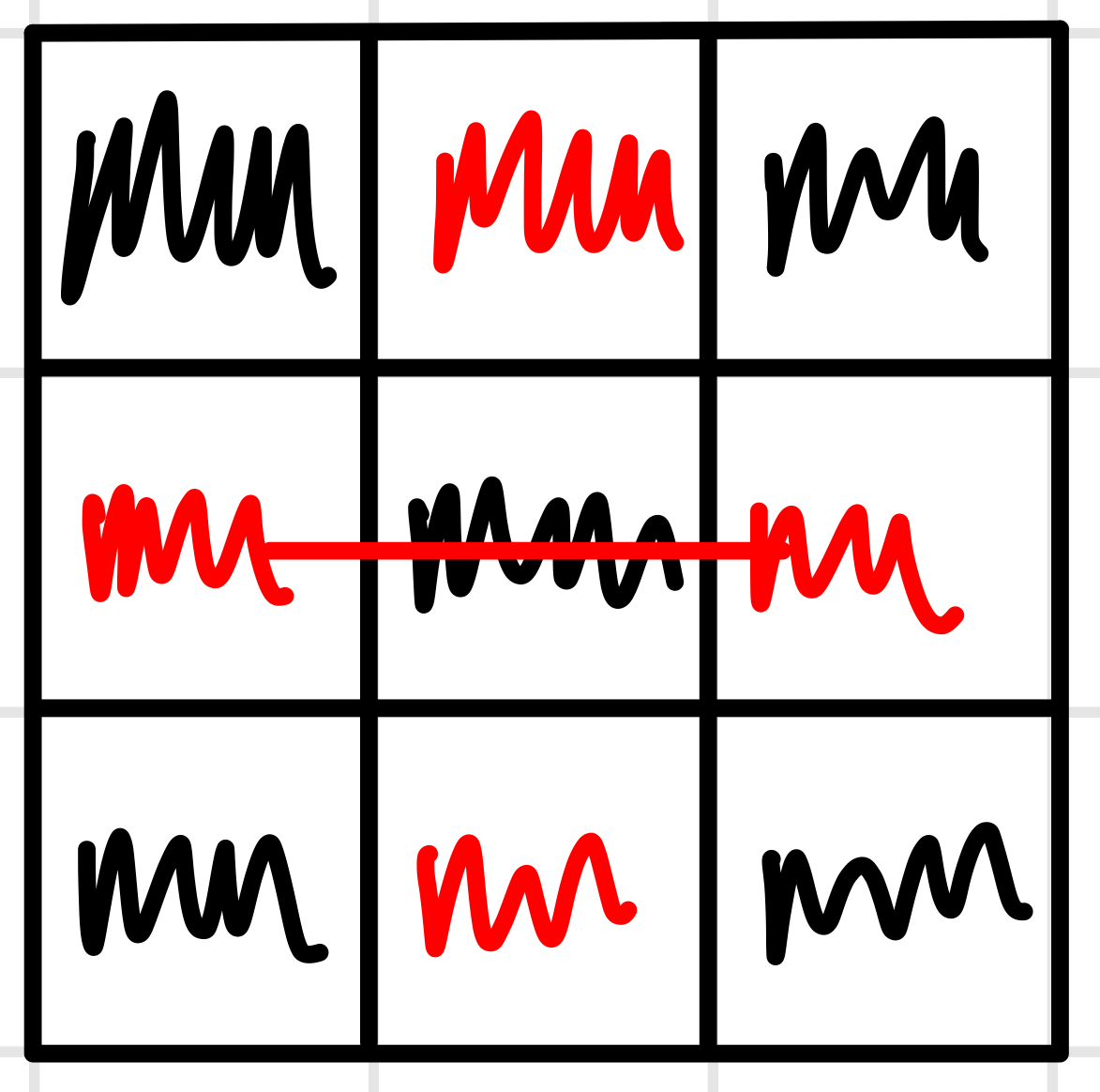

The bit twiddling readers may already see where this is going, but if we count the number of box-drawing characters we have we see there are 15. Let’s add a character that will represent a wall that has no other walls around it to bring that count up to 16. The number 16 is significant because that is how many values can be represented with 4 bits, if we include 0.

| Index | Character |

|---|---|

| 0 | ■ |

| 1 | ─ |

| 2 | │ |

| 3 | ┌ |

| 4 | ┐ |

| 5 | └ |

| 6 | ┘ |

| 7 | ├ |

| 8 | ┤ |

| 9 | ┬ |

| 10 | ┴ |

| 11 | ┼ |

| 12 | ╴ |

| 13 | ╵ |

| 14 | ╶ |

| 15 | ╷ |

If the Square is a wall it will be responsible for telling us if another wall exists in the neighboring cell to the North, East, South, or West. In fact, let’s help our WallLine out by making those cardinal directions constants.

pub const NORTH_WALL: WallLine = 0x1000000;

pub const EAST_WALL: WallLine = 0x2000000;

pub const SOUTH_WALL: WallLine = 0x4000000;

pub const WEST_WALL: WallLine = 0x8000000;

Notice that each of these constants has exactly one bit on; one bit for one of the four available bits we have for wall building. Therefore, we can think of a WallLine as a wall that we can ask the following question to: In which directions–North, East, South, and West–are your neighbors also walls? The WallLine will answer with its bits. Here is the table of all possible answers a WallLine could provide and the character we use to represent that answer.

pub static WALLS: [char; 16] = [

'■', // 0b0000 walls do not exist around me

'╵', // 0b0001 wall North

'╶', // 0b0010 wall East

'└', // 0b0011 wall North and East

'╷', // 0b0100 wall South

'│', // 0b0101 wall North and South

'┌', // 0b0110 wall East and South

'├', // 0b0111 wall North, East, and South

'╴', // 0b1000 wall West

'┘', // 0b1001 wall North and West

'─', // 0b1010 wall East and West

'┴', // 0b1011 wall North, East, and West

'┐', // 0b1100 wall South and West.

'┤', // 0b1101 wall North, South, and West

'┬', // 0b1110 wall East, South, and West

'┼', // 0b1111 wall North, East, South, and West.

];

To check the shape of a wall square we simply mask, shift, then index into this walls table.

// Make helper constants.

pub const WALL_MASK: WallLine = 0xF000000;

pub const WALL_SHIFT: usize = 24;

// Get the wall character.

pub fn wall_char(square: Square) -> char {

WALLS[((square & WALL_MASK) >> WALL_SHIFT) as usize]

}

Now as you build you will have to update the bits of all neighboring squares in cardinal directions. If you are adding a wall in a square you will need to turn on a bit for all the neighboring wall squares. If you are destroying a wall you will need to turn off a bit for all neighboring wall squares.

One Array One Maze

Because the maze conceptually represents a grid it might be tempting to create a multidimensional array.

pub struct Maze {

pub buf : Vec<Vec<Square>>,

pub rows: i32,

pub cols: i32,

}

I would actually recommend flattening this out to be a single array.

pub struct Maze {

pub buf : Vec<Square>,

pub rows: i32,

pub cols: i32,

}

And then we can use multiplication and addition to emulate the row and column based access while keeping everything in one allocation.

impl Maze {

pub fn get(&self, row: i32, col: i32) -> Square {

self.buf[(row * self.cols + col) as usize]

}

}

Your maze object is now ready to go. Modify the design to fit your needs and preferences.

Test the Walls

Your task is to now figure out how you will update squares to reflect changes in the surrounding walls during path carving or wall adding algorithms. Then, print that to the terminal in your chosen language. To check if you have correctly set up this logic I find it easiest to start with a path carving algorithm. The initial state of the maze should be all walls which will look like this.

┌┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┬┐

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

└┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┴┘

If the corners look correct, you have probably set up the wall connecting logic properly.

Conclusion

That’s it in terms of building! Now you have all the pieces in place to try your hand at implementing building however you see fit. Check out the tips at the end if you get stuck.

Implementation Tips

As promised, I will not outline how to fully implement maze building or solving. However, in my experience there are certain facts to be aware of that make the process simpler. This allows you to get to the fun stuff faster; but you are free to try to figure this out on your own.

Obtain Algorithms

If you are struggling to come up algorithms to build mazes here are some resources.

- My Maze TUI project in Rust. I have pseudocode in the wiki for every algorithm I implemented which should be relatively language agnostic.

- The Think Labyrinth website is a treasure trove of maze building information.

- Jamis Buck is a great resource for maze building ideas.

- Wikipedia can get you started on the basics.

Cursor Control

Whether you choose to build the maze in memory and then print it all at once, or come up with some real-time rendering system to watch the build process, you will need to move the cursor. In Rust this can be achieved with crates like crossterm.

// Queue the command so setting the cursor position does NOT forcefully flush for caller.

pub fn set_cursor_position(p: maze::Point, offset: maze::Offset) {

stdout()

.queue(cursor::MoveTo(

(p.col + offset.add_cols) as u16,

(p.row + offset.add_rows) as u16,

))

.expect("Could not move cursor, terminal may be incompatible.");

}

For other languages like C and C++ you may need to handle this yourself with ANSI escape codes.

inline void

set_cursor_position(const Maze::Point &p)

{

std::cout << "\033[" + std::to_string(p.row + 1) + ";"

+ std::to_string(p.col + 1) + "f";

}

These allow you to manually specify the cursor position with a string. The default position is 1 so if you use 0 based indexing add one to the position.

Build in Steps of Two

Imagine that the entire grid is a checker or chess board, where all paths start as one color and all walls the other. To carve a path or connect wall segments the goal is to connect squares of the same color by using some maze building algorithm. The algorithm will make two squares of the same color connect by “breaking” or “overwriting” the square of a different color that separates those squares in some cardinal direction: North, East, South, or West.

I would recommend leaving a perimeter wall around your maze. Path carving algorithms should always connect odd path squares by breaking down even wall squares. Wall building algorithms should always connect even wall squares by building over odd path squares. This also simplifies bounds checking for solvers.

There are other details to consider, such as if you have already “built” or “connected” a square under consideration to a square of the same type earlier in the algorithm. You can use another bit for this if you would like, but other techniques could work as well.

// walls─────────┬┬┬┐

// built bit───┐ ││││

// path bit───┐│ ││││

// 0b0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

pub type WallLine = u32;

Now you can mark every square as built, processed, finished, etc., whenever you are done building that part of the maze.

To Bit or Not to Bit

Major portions of this post are dedicated to bit manipulation and encoding. What if your language does not have these capabilities, or you don’t think the bit manipulations are worth your time? There are other strategies you can use, but I would recommend sticking with the core wall logic and create a higher level enum-like or struct-like solution to this problem. The core concepts I introduced could work exactly the same with a less space efficient approach. Here is how I might do it in Rust.

pub struct Square {

start : bool,

finish : bool,

path : bool,

wall_piece : char,

}

You can probably imagine many ways to model squares if you do not wish to use bit manipulation.