Rosetta Stones and Mazes: Solver Design

Prerequisites

Before starting, readers should

- be familiar with binary representation of numbers.

- understand some basic bitwise operations.

- be familiar with multithreading.

- be familiar with basic color theory and encoding, especially RGB and 24-bit colors.

- know if their terminals supports “true color”

Outline

By the end of this post, readers will

- be able to model maze solver processes in a variety of ways.

- be able to model multiple solving processes simultaneously.

- gain some tips for their own attempt at solving mazes with this design.

Checklist

Keeping the checklist running from the last post, this post will continue to hit language feature points.

| Hit | How |

|---|---|

| Basic Control Flow | Sequentially building a maze and solving it. |

| Associative Containers | Maze building and solving algorithms. |

| Sorting | Maze building and solving algorithms. |

| File IO | Output to terminal with stdout. |

| Standard Output | Printing maze walls and thread paths to terminal. |

| Build Systems | Setting up the project. |

| Command Line Arguments | Maze size input to program and algorithm selection. |

| Functions | Any maze building or solving function. |

| Tests | Immediate feedback from terminal. |

| Strings | Command line argument and maze character printing. |

| Common Textbook Algorithms | Maze building and solving algorithms. |

| Recursion | Maze building and solving algorithms. |

| Bit Manipulation | Maze wall and solver design. |

| Composition | Separating the program into three parts, maze design, maze building, and maze solving is an example of composition. Consider creating one modules for each part and passing the maze to the builder and solver. |

| Multithreading/Processes | Maze solver design. |

| 3rd Party Libraries | |

| Type Creation | Maze wall design. |

| Interface Design | Keeping the maze object simple and passing it to a builder and solver interface that accept a maze is a good idea. This means the builders and solvers expose their own interfaces. |

| Trees | Maze building and solving algorithms. |

| Stacks | Maze building and solving algorithms. |

| Heaps | Maze building algorithms. |

| Queues | Maze solving algorithms. |

| Graphs | Maze building and solving algorithms. |

| Multidimensional Arrays | Maze square storage. |

| Fun! | All of it! |

Trapped in the Labyrinth

At this point you have likely tried your hand at maze building. This is a deep and interesting topic with some advanced algorithms and data structures to implement. However, the program likely feels incomplete without the final step of actually solving the maze. We will now take the final step to complete the Rosetta Stone maze program and design the solver(s).

Augment the Square

Recall from the last post the design of our Square type.

// walls─────────┬┬┬┐

// built bit───┐ ││││

// path bit───┐│ ││││

// 0b0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

pub type Square = u32;

If you followed the tips at the bottom of the last post you also made use of an additional bit to mark when building a section of the maze was complete. However, we still left many of the bits unused. Now it is time to use them all.

Start and Finish

Let’s add the ability to make a square the start or finish of the maze.

// walls───────────┬┬┬┐

// built bit─────┐ ││││

// path bit─────┐│ ││││

// start bit───┐││ ││││

// finish bit─┐│││ ││││

// 0b0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

pub type Square = u32;

Counting from the 0th least significant bit we now have the 30th bit as the start marker and the 31st bit as the finish marker. To begin the solving process, you first select a random start and finish point in the maze. How you display those points is up to you, but it will look something like this (I use S for start and F for finish).

┌───────────┬───┬─┬───┬─────────┬───┬─┬─┬───┬─┐

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

├─┬─╴ ╶─────┤ ╶─┘ └─╴ ╵ ╶─┐ ╶─┐ └─┐ ╵ ╵ └─╴ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ ├─╴ ┌───╴ ╵ ╶─┬─╴ ╶─────┴─┐ └───┤ ┌───╴ ╶─┘ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ F │

│ └───┤ ┌─┐ ╶─┐ └─┬─┐ ╶─┐ ╶─┤ ╶───┘ ├───┬─┬─╴ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

├─┐ ╶─┘ │ └─┐ │ ┌─┘ │ ╶─┤ ╶─┴─┬───┐ ╵ ╷ │ ├─╴ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ ├─┐ ╷ └─╴ │ └─┤ ╶─┘ ╷ └─┬─╴ ├─┐ └───┼─┘ └─┬─┤

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ ╵ ├─┐ ╶─┴─┐ ├───┬─┴─┐ ├─┐ ╵ ╵ ╷ ╷ ╵ ┌───┘ │

│ │ │S│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ ╷ ╵ ├───┐ └─┘ ╷ │ ╷ ╵ │ └─╴ ╶─┤ │ ╷ ├─┐ ╷ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ └─┘ ┌─┘ ╷ ╵ ┌───┘ │ │ ╷ ├───────┴─┘ │ ╵ └─┘ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

└─────┴───┴───┴─────┴─┴─┴─┴───────────┴───────┘

Solver Bit

I will again recommend using one of the bits in our square to remember where the solver has visited. Remember that we have one bit that marks a square as a path. If the bit is on, the square is a path. If bit is off, the square is a wall. A helpful insight is that when the square is a path the four bits we usually use to describe the wall shape are unused. We can use one of them to indicate a solver has visited the square.

// solver bit─────────┐

// walls───────────┬┬┬┤

// built bit─────┐ ││││

// path bit─────┐│ ││││

// start bit───┐││ ││││

// finish bit─┐│││ ││││

// 0b0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

pub type Square = u32;

Here the solver can mark visited squares with the 24th bit.

Solver Color

We still have the lowest 24 bits to work with. Let’s add 24-bit RGB color for the solver.

// blue bits────────────────────────────────┬┬┬┬─┬┬┬┐

// green bits─────────────────────┬┬┬┬─┬┬┬┐ ││││ ││││

// red bits─────────────┬┬┬┬─┬┬┬┐ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││

// solver bit─────────┐ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││

// walls───────────┬┬┬┤ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││

// built bit─────┐ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││

// path bit─────┐│ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││

// start bit───┐││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││

// finish bit─┐│││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││

// 0b0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

pub type Square = u32;

There are many techniques to print color to the screen, but they often revolve around isolating these three colors into an RGB tuple or array. In Rust that could be done like this.

// Make constants for convenience.

pub const RED_MASK: maze::Square = 0xFF0000;

pub const RED_SHIFT: maze::Square = 16;

pub const GREEN_MASK: maze::Square = 0xFF00;

pub const GREEN_SHIFT: maze::Square = 8;

pub const BLUE_MASK: maze::Square = 0xFF;

// Obtain colors through masks and shifts.

fn get_rgb(square: maze::Square) -> (u8, u8, u8) {

(

((square & RED_MASK) >> RED_SHIFT) as u8,

((square & GREEN_MASK) >> GREEN_SHIFT) as u8,

(square & BLUE_MASK) as u8,

)

}

If a method for color printing takes the hex value for colors then simply masking and obtaining the bottom 24 bits would work.

Now the solver can stamp each square it visits with its color via a bitwise OR operation.

square |= COLOR;

The solver can also remove its color from a square while backtracking via a bitwise AND operation.

squrae &= !COLOR;

These two operations allow you to visualize many solving algorithms.

Multiple Solvers

You now have all the pieces you need to implement the full Rosetta Stone maze program. In fact, when you use this program to try new languages, all we have discussed so far is a good stopping point if you are short on time. But I promised this series would discuss how to check off all of the items in the Hit and Miss columns of the first post so we can now start discussing more advanced features to pursue.

If the language you have chosen has multithreading capabilities, we can explore them with maze solvers. Instead of one solver, let’s make four.

// blue bits────────────────────────────────┬┬┬┬─┬┬┬┐

// green bits─────────────────────┬┬┬┬─┬┬┬┐ ││││ ││││

// red bits─────────────┬┬┬┬─┬┬┬┐ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││

// solver bits─────┬┬┬┐ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││

// walls───────────┼┼┼┤ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││

// built bit─────┐ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││

// path bit─────┐│ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││

// start bit───┐││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││

// finish bit─┐│││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││ ││││

// 0b0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

pub type Square = u32;

Now bits 24-27 are used, one for each solver that visits a square. We are intentionally creating contention over a resource to test how our chosen language enforces protection of shared resources while multithreading. In Rust, we can design protections around the maze for multiple threads as follows with the monitor technique.

use std::{

sync::{Arc, Mutex},

};

pub struct Monitor {

pub maze: maze::Maze,

pub win: Option<usize>,

pub win_path: Vec<(maze::Point, maze::Square)>,

}

impl Monitor {

pub fn new(boxed_maze: maze::Maze) -> Arc<Mutex<Self>> {

Arc::new(Mutex::new(Self {

maze: boxed_maze,

win: None,

win_path: Vec::default(),

}))

}

}

pub type MazeMonitor = Arc<Mutex<Monitor>>;

- The maze is protected in the monitor.

- We are tracking the winning thread index to the finish with ID 0-3.

- We will make the winning thread record the path it took to the finish in the monitor

Vec.

Different languages will likely approach the concept of mutual exclusion and multiple threads differently. However, a monitor is a simple design that works for many multithreading abstractions.

Color Theory

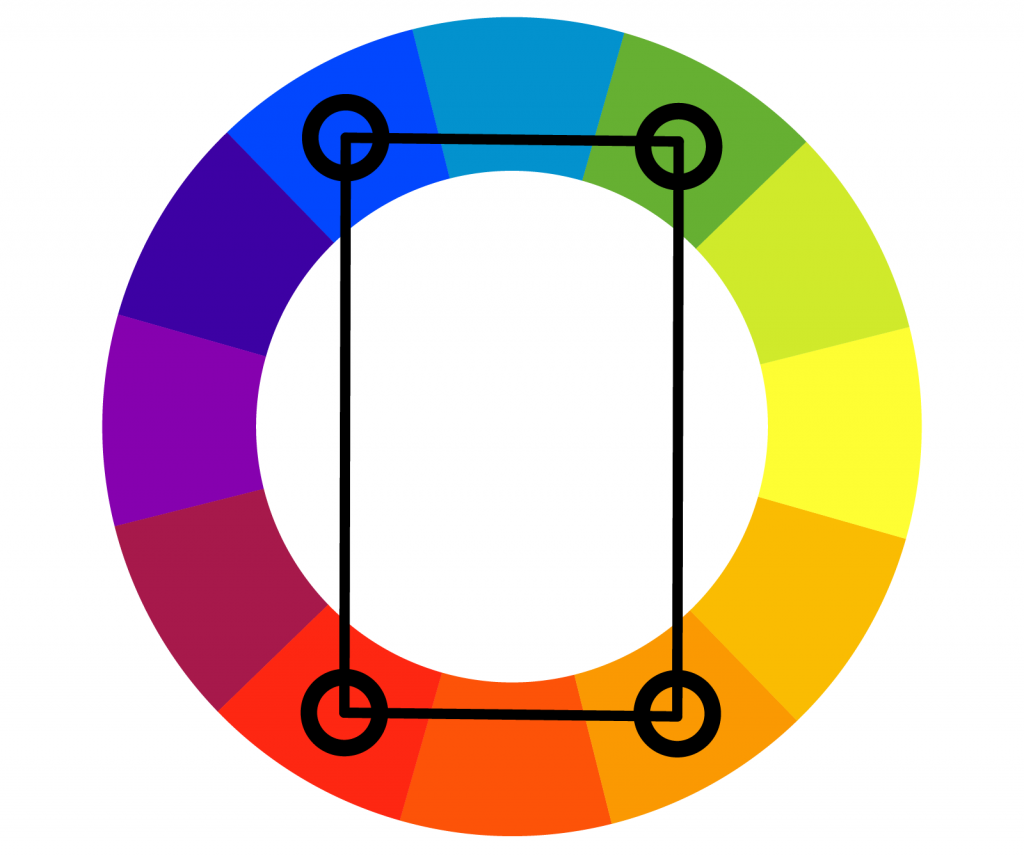

The final detail we need to manage is how multiple threads can leave their color marks on a square if the square only has 24 bits available. For this, we can look to the color scheme concept of Tetradic colors.

A Tetradic color scheme is one in which four colors compliment one another by sharing a 90 or 180 degree relationship between one another. This effectively forms a rectangle of colors that balance and complement each other well.

Because we have 24 bits, and 4 threads, we must choose four RGB colors with an interesting property: the colors cannot have any bits that overlap. Some maze solving algorithms use backtracking, so when a thread backtracks and removes its color from a square, representing its path, we must clean up its bits. This is a case where we need idempotence; we can’t have side effects and the effect of stamping a color or removing a color must be the same if applied multiple times, regardless of the presence of other color stamps at the square.

If four threads have visited a square, and we only care about their colors, the result is as follows.

let square = COLOR_1 | COLOR_2 | COLOR_3 | COLOR_4;

If any thread backtracks and removes its mark from this square, the following statements must be true.

assert!((square & !COLOR_1) == (COLOR_2 | COLOR_3 | COLOR_4));

assert!((square & !COLOR_2) == (COLOR_1 | COLOR_3 | COLOR_4));

assert!((square & !COLOR_3) == (COLOR_1 | COLOR_2 | COLOR_4));

assert!((square & !COLOR_4) == (COLOR_1 | COLOR_2 | COLOR_3));

When removing any color all remaining colors must remain unaffected. It is easy to come up with random color values with this property, but hard to come up with four colors that look good and are visually distinct. I was stuck for a while until I asked an embarrassingly down-voted StackOverflow question and a kind soul helped me find four colors that satisfy this property.

// Credit to Caesar on StackOverflow for writing

// the program to find this tetrad of colors.

pub const THREAD_MASKS: [maze::Square; 4] = [

0x880044, 0x766002, 0x009531, 0x010a88

];

Now there are four unique colors that will mix creating 15 possible unique colors depending upon the number of threads that visit a square. As an added bonus, the more threads that visit a square the brighter the colors get which acts as a kind of heat map of thread activity.

I went to all of this trouble because using 24-bit color allows us to specify the exact color that should appear on solving paths regardless of any terminal style settings we may have on our computers.

Conclusion

You now have all the tools to implement a program that both builds and solves mazes. We even went above and beyond with the more advanced multithreading design. You should alter the design to fit your language capabilities and time constraints. See the tips at the bottom of the post if you get stuck. I am refraining from showing what a finished product should look like in this post so as not to spoil the satisfaction of creating these visuals yourself.

In the next and final post in this series we will discuss why this Rosetta Stone project is good for testing third party libraries in a language and some advanced ideas to pursue.

Implementation Tips

Again, I will not spoil implementation details for the solvers. However, I can leave some ideas that may simplify the process of building this part of the program.

Obtain Algorithms

Similar to maze building algorithms, maze solving algorithms will introduce you to a rich field of computer science theory. There are two main solving algorithms to pursue.

- Depth first search.

- Breadth first search.

Each has its own unique characteristics that are worth learning about. However, if you continue to research graph related algorithms, you will likely encounter these as well.

- Dijkstra’s.

- A* (A-star).

For these more advanced algorithms to make use of their additional logic, you may need to alter how the solvers interpret paths and weights in the maze. Or, you might need to perform more passes over the maze before solving. As you learn more about these types of algorithms, see if you can answer these questions about the maze.

- What are the nodes in a maze?

- What are the edges in a maze?

- What are the weights of the edges in a maze?

Compose the Process

You are free to design this program in whatever way you enjoy. However, I think there is an easy and extendable way to approach things.

Keep the maze object simple; it is just an integer and can expose the raw materials you have to work with to build walls, specifically the box-drawing characters. Then the program flow can look something like this.

solve( build( new_maze( args ) ) )

The maze allocates memory for its squares, the builder molds those squares to its liking, and the solver expects a perfect maze to solve. You can then add numerous functions that build and numerous functions that solve in different sections of your program or in different files. Each part of the process on its own remains simple, but these parts compose together to finish a complicated process.

Simpler Colors

The 24-bit color idea is somewhat advanced. Instead, we can take an approach more in line with our wall design from the last post. However, it requires more hand coding. Instead of 24 bit colors, just use a single bit to represent the paint of a thread (my C++ version of this program uses this method).

/// wall structure----------------------||||

/// ------------------------------------||||

/// 0 thread paint--------------------| ||||

/// 1 thread paint-------------------|| ||||

/// 2 thread paint------------------||| ||||

/// 3 thread paint-----------------|||| ||||

/// -------------------------------|||| ||||

/// 0 thread cache---------------| |||| ||||

/// 1 thread cache--------------|| |||| ||||

/// 2 thread cache-------------||| |||| ||||

/// 3 thread cache------------|||| |||| ||||

/// --------------------------|||| |||| ||||

/// maze build bit----------| |||| |||| ||||

/// maze paths bit---------|| |||| |||| ||||

/// maze start bit--------||| |||| |||| ||||

/// maze goals bit-------|||| |||| |||| ||||

/// 0b0000 0000 0000 0000

using Square_bits = uint16_t;

If a thread visits a square, it will turn on its paint bit. If it leaves, it turns it off. Because there are 4 bits, we have 16 possible combinations of colors, including 0. Hand pick those colors as ANSI color escape sequences.

constexpr std::string_view ansi_red = "\033[38;5;1m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_grn = "\033[38;5;2m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_yel = "\033[38;5;3m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_blu = "\033[38;5;4m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_prp = "\033[38;5;183m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_mag = "\033[38;5;201m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_cyn = "\033[38;5;87m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_wit = "\033[38;5;231m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_prp_red = "\033[38;5;204m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_blu_mag = "\033[38;5;105m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_red_grn_blu = "\033[38;5;121m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_grn_prp = "\033[38;5;106m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_grn_blu_prp = "\033[38;5;60m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_red_grn_prp = "\033[38;5;105m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_red_blu_prp = "\033[38;5;89m█\033[0m";

constexpr std::string_view ansi_dark_blu_mag = "\033[38;5;57m█\033[0m";

Then place them in a table in a way that will be visually appealing.

// Threads Overlaps. The zero thread is the zero index bit with a value 1.

constexpr std::array<std::string_view, 16> thread_colors = {

ansi_no_solution,

ansi_red, // 0b0001

ansi_grn, // 0b0010

ansi_yel, // 0b0011

ansi_blu, // 0b0100

ansi_mag, // 0b0101

ansi_cyn, // 0b0110

ansi_red_grn_blu, // 0b0111

ansi_prp, // 0b1000

ansi_prp_red, // 0b1001

ansi_grn_prp, // 0b1010

ansi_red_grn_prp, // 0b1011

ansi_dark_blu_mag, // 0b1100

ansi_red_blu_prp, // 0b1101

ansi_grn_blu_prp, // 0b1110

ansi_wit, // 0b1111

};

Now there is a unique color combination for every combination of thread path that is actively over a square. To print, we just check if any color bits are on and then print them out.

constexpr uint16_t thread_paint_shift{4};

constexpr Thread_paint thread_paint_mask{0b1111'0000};

if (square & thread_paint_mask)

{

const Thread_paint thread_color =

(square & thread_paint_mask)

>> thread_paint_shift;

std::cout << thread_colors.at(thread_color);

}

To Bit or Not to Bit

We again have designed a large part of the program to use bit manipulation. If you would rather use a more Object-Oriented Design with a struct, here is how I might do it in Rust.

pub struct Square {

start : bool,

finish : bool,

path : bool,

path_rgb : [u8; 3],

wall_piece : char,

}

Now that you have all the information to implement the program, there are many other possible designs one could use for the maze squares.